Retail Finance 101: Why your e-com finance team may not be equipped for retail

Finance gets notably more complicated when you introduce a retail channel to your business

The tl;dr

Retail channels’ economics are far more complex than those of other channels

Applying finance, accounting, and even excel modeling principles and skills from pure e-commerce to retail doesn’t work

Retail Finance is a specialization within the broader Finance function that needs to understand the nuances of lease accounting rules, unit economic modeling, and various expense classifications

Learn how to build an automated financial model for retail expansion below (including a link to download)

Starting with the basics: Retail Finance

I often refer to 4 core areas of retail:

Retail Strategy & Finance

Real Estate & Lease Administration

Store Design & Construction

Store Operations & Leadership

Strategy & Finance may sound odd to call out because they exist in many other contexts outside of retail, while the other functions are specific to stores. But they’re important skillsets, if not entire functions, that should exist in a business with stores.

That said, “strategy” is a skill and function that every company has in varying capacities, and it’s no surprise that Retail also has its own distinct definition.

Finance, on the other hand, may not be so obvious. While it’s not as nebulous as “strategy” (which is generally afforded some flexibility as to what it means who is qualified to have that title), it comes with more technical qualifications like knowledge of specific accounting principles.

Put another way, even if your Finance lead has 20 years of experience with e-commerce brands, they may still have 0% experience in the specifics of Retail Finance (this has been my experience with e-com Finance leads).

In my experience, a Retail Finance lead generally has an understanding of the below unique subject matters:

Store P&Ls and unit economics*

GAAP accounting principles*

Lease accounting

Project capitalization rules

Cash vs non cash expense reconciliations

Dynamic modeling techniques*

I’m not going to touch on the last topic (capital planning) since I covered that in a past issue.

Breaking it down: overhead and unit economics

A key to successfully building, running, or even winding down a business is understanding it’s financial operating requirements.

In retail, as in most businesses, there are two primary sets of financials to understand:

Overhead: typically non-revenue generating, and generally fixed costs. Examples of some of the big cost buckets for retail channels include:

Corporate team payroll: store development team, head of retail, district/regional managers

Technology: GIS, project management software, store communications/intranet software, etc.

Professional Services: brokers, project managers, management consultants

Travel: store visits, real estate site tours, industry conferences

Events: broader team conferences

Training: team Learning & Development

In aggregate, this collection of expenses is usually referred to as a department budget, opex, or G&A (general and administrative) expenses.

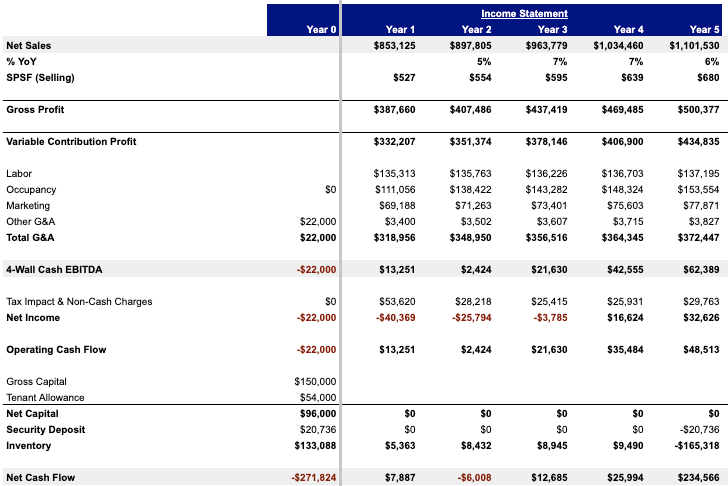

Unit economics: typically refers to the economics of the average store, or “unit”; synonymous to marketers’ evaluations of a single customer’s lifetime value, or a sales leader’s view of the profitability of an average sale. The idea is that the cumulative profits from each individual unit will cover the overhead, and eventually create an overall profitable business (or in this case, a profitable channel). This is generally viewed through the lens of a store P&L:

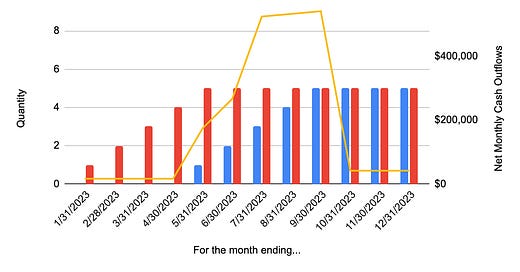

Even within a store, the same general structure applies: overhead is the Total G&A and is mostly comprised of fixed costs, while the “unit economic profile” typically refers to the Net Cash Flow or 4-Wall Cash EBITDA and associated % of Net Sales.

This might be basic for a lot of folks, but here’s a quick rundown of what each of these line items mean:Net Sales: This is after accounting for returns and discounts. While it’s not shown above, it’s important to monitor the haircut of a store’s Net Sales from Gross Sales across locations and channels. Just because a store is growing, doesn’t mean the sales are healthy.

Gross Profit: The net cash generated after accounting for the cost of manufacturing and shipping the orders

Variable Contribution Profit: The net cash generated after accounting for the cost of driving the sale. Generally this refers to the Merchant Processing Fees, and sometimes can include allocated direct marketing costs, or commissions.

Labor: Salaries, bonuses, cost of benefits; includes overtime. All of these should be broken out and monitored separately by a combination of Finance and HR.

Occupancy: This typically refers to the costs of “occupying” the space, including rent, cleaning services, utilities, maintenance, etc.

Marketing: Should only include direct marketing costs, and not allocations if you’re method is to do so using % of total company sales. In-store events, or local marketing initiatives are the primary components of this.

Other G&A: Catch-all for everything else, which is typically travel costs, one-time new store set up costs, and technology services (eg traffic counters).

4-Wall Cash EBITDA: This is arguably the most important unit economic metric to observe, since it answers investors’ biggest question: do your stores make money or not once they’re up and running.

Net Income: Public companies care more about this than startups, but is the proper GAAP definition of “profit.”

Operating Cash Flow: Reflects the impact of taxes.

Net Cash Flow: Though I think 4-Wall Cash EBITDA is the most important, Net Cash Flow is a close second. It answers the same question, but takes into account how much the store costs to build in the first place. You ultimately need to have a solid understanding of both.

Now for the more technical stuff: GAAP accounting

I’m not an accountant, so I’m not going to pretend to be. But I will highlight the areas where a typical Finance/Accounting lead who hasn’t worked in brick and mortar retail might have a gap in knowledge.

Accounting is the technical practice of properly classifying, tracking and pairing revenues with associated expenses. A big part of this is knowing how to reflect certain things in your financial statements in accordance with GAAP: Generally Accepted Accounting Principles. This is essentially the set of rules that businesses must follow to ensure internal and external folks can properly understand what’s going on with your business.

This is especially important for a business that operates stores: leases have a number of special accounting treatments that affect how the numbers show up in your financial statements.

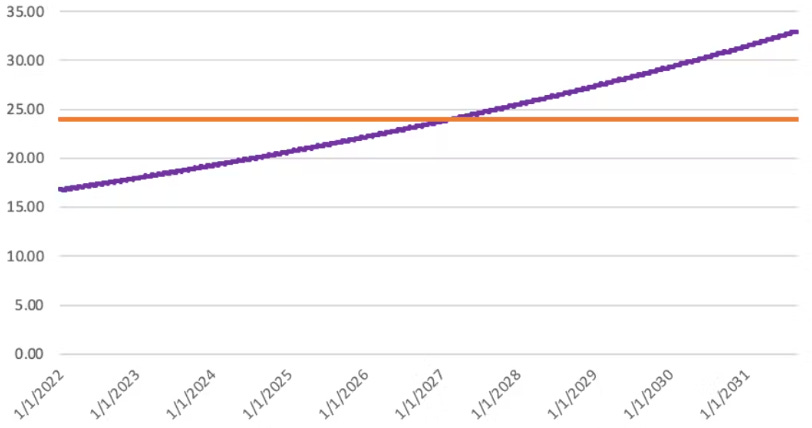

For example, a common rent arrangement is to charge a price that grows at some percentage every year (the purple line). But GAAP accounting would actually reflect the same average rent price every year of the lease (orange) — this is commonly referred to as “straight line rent”:

And this is just scratching the surface of lease accounting complexities. If you want to learn more, read about out ASC 842. These rules are constantly changing (particularly right now), so even your accounting department needs to be plugged into these principles.

While knowing how to do proper accounting isn’t the Retail Finance person’s job (that’s on Accounting), they need to know “it’s a thing.” I’ve worked with Finance leads and even CFOs who don’t know that the reason their rent is the same every year in their P&Ls is because of an accounting rule, and therefore misforecast cash flow (on P&L the rent looks flat, but on a cash basis it’s growing).

I won’t repeat it here, but the timing of when these expenses start (on both cash and non cash basis) are also tied to certain milestones of a lease’s negotiation progress.

And last but not least, it’s also important to understand the concept of capitalization. Unlike marketing spend, a significant portion of growth investments in stores is into a physical asset: meaning GAAP accounting treats it a little differently too.

Generally speaking, if the “thing” you’re spending money on will last for more than a year, then you capitalize it. This means you consider it an investment rather than expense — which is important as you manage the optics of your business. Expenses hurt your EBITDA, capital investments don’t. I’m leaving out a lot of other complexities and tradeoffs, but that’s the most important callout for startups as they have to invest via expenses vs capital — and it’s all related to accounting.

Put another way, if you spend $1,000,000 on marketing, then your profits decline by $1,000,000. If you spend $1,000,000 on a capital investment (eg stores), your profits DON’T decline by that amount.

You likely need to step up your excel modeling skills if you’ve only experienced Finance in an e-commerce setting

Most DTC startups truthfully don’t have complicated enough revenue streams to require complex excel modeling. The most common sales forecasting for DTC brands — assuming a single, e-commerce channel — tends to look something like this:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Clicks to Bricks: The Playbook to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.