The tl;dr

Most DTC execs don’t fully understand the data gold mine they’re sitting on

Many leaders and analysts use DTC data to answer company-first questions: which products/channels are performing, etc.

Leaders should be using it to answer customer-first questions: which customer segments are the largest/growing the fastest, etc

Leveraging customer address data can help you identify who your customer really is — and isn’t — and where you can find more of them

Most DTC execs don’t fully understand the data gold mine they’re sitting on

DTC brands and reporters love mentioning “the power of DTC brands’ data,” but I rarely hear exactly what they mean and how it’s different than most non-DTC models.

And when I talk to DTC brand execs about which data points they look at, it’s truthfully nothing exciting:

Sales by product category

Customer acquisition cohorts

Customer lifetime value analysis

New vs repeat attributes

Sales by channel

While some of these scratch the surface of DTC’s power, they’re not taking advantage of an even more powerful data field: the customer’s address.

The power of geography

I’ve written about this topic at a higher level before:

A (not so) new foundation for retail metrics: Geography (Part I)

The (not so) new foundation for retail metrics: Geography (Part II)

But in this newsletter I’m going to share some actual case study examples of when I used this type of DTC data to identify impending strategic failures and risks:

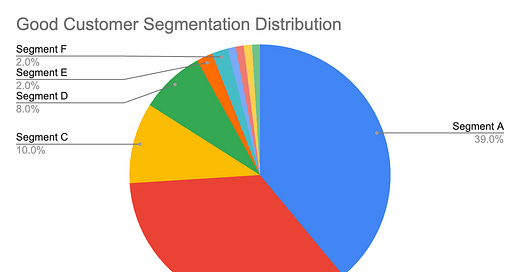

Example 1: The brand primarily catered to a certain demographic segment of customers, and felt that it had saturated that persona. And in an attempt to capture “new” personas, there was a mandate to shift the real estate strategy to target new markets. In short, they felt that new markets held more opportunity for growth than existing markets. (Hint: they were wildly wrong)

Example 2: The brand felt that it was succeeding in its reinvention: new marketing and merchandising strategies had supposedly come a long way, and it was time to open stores for this new cohort of customers. I expressed concerns that their customer base was still too scattered: their brand was objectively a little bit of everything to everyone, which means it’s really nothing to no one. Ignoring my concern led to millions of dollars in mistakes.

Example 3: The brand had enough capital to invest in one more market, and had to choose between two options. The real estate was priced the same between the two opportunities, but I felt one market had far more upside than the other. I got pushback from the brand team, and the reason was surprising — which I was able to extract from them after doing an analysis that can only be done with first party geographic data.

Here’s how I did it

Example 1: How I predicted the failure of a new market expansion strategy

I discovered a really powerful correlation pretty early on: a brand’s e-commerce data is the most predictive variable for a new store’s success. Here’s what that literally looks like in a chart with dummy data:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Clicks to Bricks: The Playbook to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.